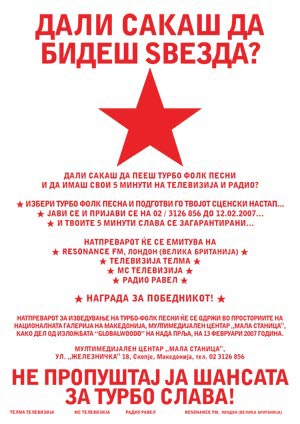

Nada had a solo show at the National Gallery of Macedonia, Skopje (February 2007). Here are some images from that exhibition, which included a competition for a new Turbo Folk star. Nada and I had a discussion on Resonance fm on her return to London with Skart about Turbo Folk and pop culture in south east Europe (http://www.resonancefm.com/). Also, see below for a text I've written about Nada's work for her catalogue.

Confessions of a music fan.

by Sophie Hope (February 2007)

I have got a confession to make. When I was younger I was madly and passionately in love with New Kids on the Block (NKOTB). I went to see them live three times, dragging my loyal, suffering, paying mother to different parts of the UK in order to do so.

Step by step ooh baby

Gonna get to you girl

Step by step ooh baby

Really want you in my world

Hey girl in your eyes

I see a picture of me all the time

And girl when you smile

You got to know that you drive me wild

(Step by Step, 1990)

Of course I believed these words whole-heartedly. Their tactic worked as millions of other young dungeree-wearing spotty girls thought the boys had invented these lyrics for them too. Did I have blind faith in this manufactured boy-band because I was really stupid or was there something else going on? It was not damaging for me to like this music. I was growing-up.

To what extent is the music we listen to harmless fun, propaganda or inciting violence? Pop impresario Maurice Starr cleverly tapped into the minds of pre-pubescent girls to make a lot of money by kindly giving the world NKOTB. You will be glad to hear I shunned NKOTB and went on to become a grumpy grunge teenager. KoRn are a more current version of what I had moved onto. Their songs also tap into an angst-ridden generation:

Day, is here fading

My time, has gone away

I flirt with suicide

Sometimes kill the pain

(Falling Away From Me, 1999)

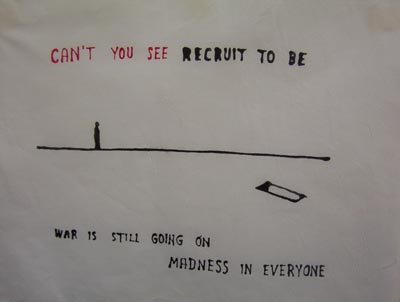

Listening to music is a sole-searching exercise which most of us enjoy doing with a good sized dose of salt. We revel in the seriousness of this exercise and the utter absurdity of it. Bands such as Azra, Idoli and Disciplina Kicme that were part of the Yugoslav New Wave musical trend in the early 1980s embodied a self-awareness appreciated by many young people growing up in post-Tito Yugoslavia. The music provided an anti-establishment satire of Yugoslav socialism that was to some extent tolerated by the communist authorities.

While New Wave was enjoyed as an ‘avant-garde’, independent critique of society, the popular music of the early 1990s known as Turbo Folk became the official music of ‘paramilitary nationalism’. Still going strong, the music is now termed Pop Folk as its obsession with a glamorous lifestyle has replaced Turbo Folk’s overtly nationalistic messages. The music cleverly combines both exaggerated enthusiasm for rampant consumerism and latent nationalistic nostalgia. While the short-lived Yugoslav New Wave scene maintained a healthy suspicion of everyone and everything (communism and capitalism), Turbo Folk seems to devour it all.

What does it mean then for Nada Prlja to host a Turbo Folk competition as part of her exhibition, GLOBALWOOD? In drawing attention to the phenomenon and perhaps blind faith in turbo culture, this exercise attempts to draw attention to the absurd side of this music.

Whenever your night is long

Wine will make it shorter.

Start having a feast

Another day is on its way.

Oh brothers and sisters,

One day God will pay us back

For living this life as we do

As if it was a dream.

Jelena Karleusa, Pa Naravno, 2005

This competition offers us a chance to laugh at turbo-folk, enjoy it, hate it, but also understand that it is not the music but what it represents that makes this event so important. Turbo-folk is a contemporary symbol of a society in the throws of transition towards a self-absorbed, fake-tanned capitalist world. Despite its outwardly materialistic image, however, the use of eastern melodies is also seen as an anti-globalisation statement that has currency in the West. The schizophrenic musical result presents a coping strategy to enjoy this tension between the lure of both the local and global.

By putting on this event, Nada is asking both contestants (turbo-folk fans) and judges (artists and intellectuals) to face each other and confront the fact that they both take themselves perhaps a bit too seriously. One embraces the popular and ‘sexy’ image of turbo folk, the other dismisses it as superficial. I can imagine this scene, in which both performers and judges play their part is uncomfortable, but at the same time irresistible to watch. We, the audience are therefore implicated in the performance and have to recognise our own nervous, submissive state. We are sucked into the spectacle.

While there is an element of humour and irony in the competition, there is a more serious side. This action is not about persuading all people to dismiss turbo-folk. Instead, we are being asked to question our own beliefs and passions and recognise the twists and fates of our choices. There is a reason why turbo-folk taps into the life blood of a generation, culture or character. Revealing and dealing with those reasons is also a process of realizing the implications of our blind faith or alternatively complete dismissal of turbo-folk and all it represents.

How can the competition as an art event begin to ask these questions? Sometimes it takes a repetition or re-enactment to create a fraction of distance enabling us to question our actions and our listening tastes. At the time of my obsession with NKOTB I was unable to comprehend a future without them. An act such as the Turbo Folk / Pop Folk competition could be understood as an advert or celebration of Pop Folk. If it sets out to undermine the music, its fans would be reluctant to take part. They are unable to distance themselves from the music and so any manifestation of it is a welcome treat. What is the point then of such an exercise if only a few are in on the ‘joke’? Maybe it takes time for the critique to settle in.

I worked with Nada on her project, Advanced Science of Morphology which saw the blended flags of the countries of the former Yugoslavia flying in Marble Arch Park for two weeks in June 2006. We got permission from Westminster Council to remove the existing flags of the countries of the European Union and replace them with Nada’s new designs. There are many different readings of this action. By replacing the EU flags with those of countries on the margins of the EU (to date, of those countries of the former Yugoslavia only Slovenia is in the club), we are drawing attention to the power play across nations. We are giving some of the ‘Balkan’ nations a temporary, symbolic platform in a ‘centre of Europe’ – London. By doing this, we are also highlighting how problematic such a display of nationhood is. The fact that the flags do not represent the individual countries’ flags, but morph their emblems is a take on the fluidity and ambiguity between nations. To me, it questions the notion of nationhood in the first place. This is highly problematic as we are questioning and undermining an idea that many place utmost importance in to the extent that they will die or kill in order to maintain it.

While these are valid questions, what is the best way to ask them without the work itself becoming a nationalistic symbol? Journalists in Macedonia reacted to the installation in Marble Arch with nationalistic pride. One headline read:

'Our artist has pulled down the EU flags in the centre of London'

Is this a reflection of the media’s reluctancy to reflect critically on what it might mean for their flags to be morphed with symbols of neighbouring nations? Do you need to be at a distance (temporally and, or spatially) to ask these questions? While this may be the case, it could be argued that distance of time and place cancel out the potential for the action to have a knock on effect in the place it matters. But where does it matter? Advanced Science of Morphology asks questions of territorial claims and hierarchies across Europe. It is not just relevant in south east Europe but tells us something about Britain’s way of dealing with the wider context of European identities. The same Macedonian newspaper goes on to print:

'The EU fears Balkanization'

As a continuation of Advanced Science of Morphology, Nada’s new work, ‘Localn Globalism’, presents records painted with the colours and symbols of the flags of Albania, Bulgaria, Greece, Macedonia, Romania, Sebia, and Turkey play music based on the words ‘localism’ and ‘globalism’. Songs from these countries feature the most on the turbo-folk TV channel, Balkania. The absence of Bosnia, Croatia, Montenegro and Kosovo from this list reveals the power play between nationalities presented to us in everyday life. Manifestations of nationality are expected and normalised, whether that is through national symbols such as flags or in the lyrics of pop culture. Nada’s GLOBALWOOD presents the power of these symbols. It is the different interpretations of them that can reveal our fears, insecurities and dreams.